What makes us feel hurt?

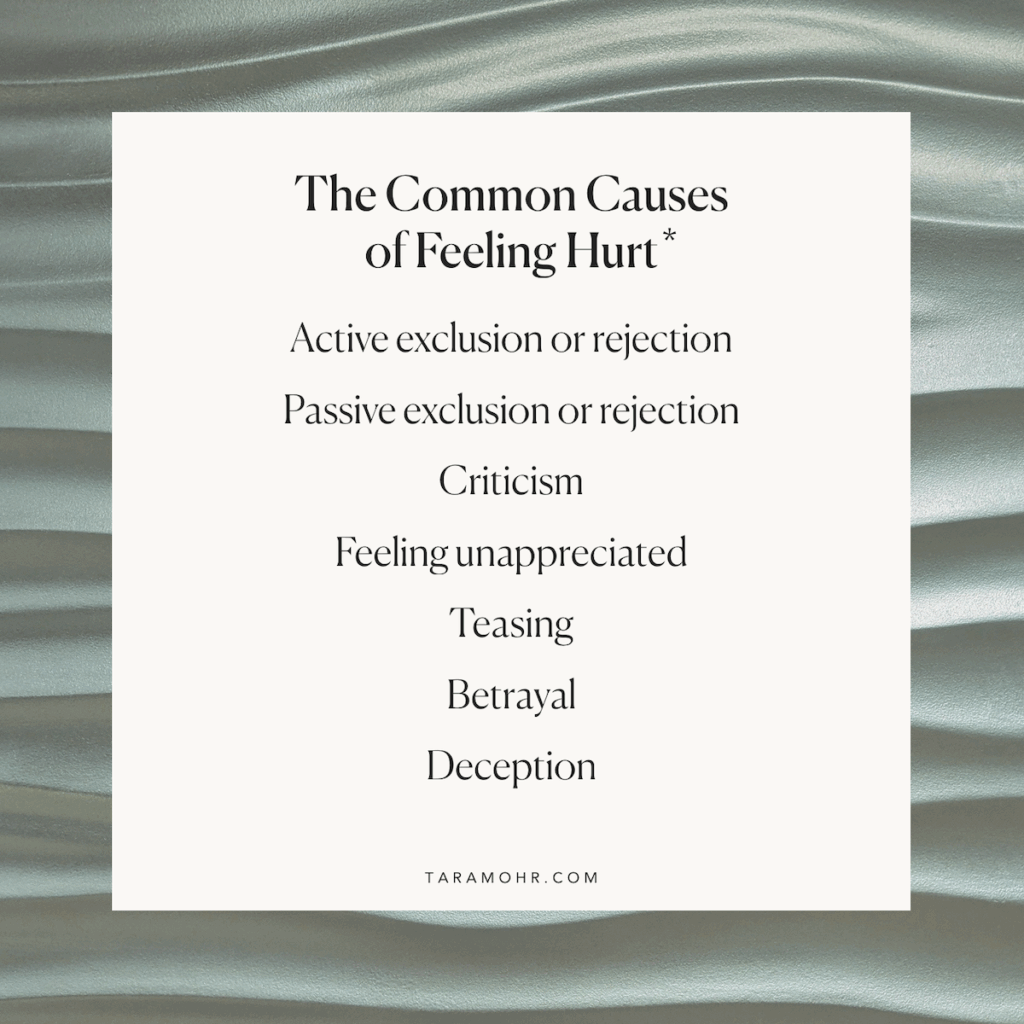

Psychology researchers have sought to come up with a list of the causes of feeling hurt. They created that list for further research and study on the types of hurt, but I immediately grabbed onto that list as itself a kind of personal growth tool. I find it immensely useful in my own life, and in my coaching.

The idea here is not that we always feel hurt when we experience these things. The idea is that when we do feel hurt, usually one of these is the cause.

• Active exclusion or rejection. These are experiences of outright rejection, exclusion or ostracism that cause us to feel hurt. For example, not being invited to a friend’s small birthday gathering, or being broken up with by a partner, or being a final candidate for a job and not being the one to get it. We all know it from our own life experience – rejection or being left out can really hurt.

• Passive exclusion or rejection. These are more subtle experiences of exclusion, or things we may interpret as rejections, for example, “They didn’t even invite me to sit down with them,” or “She stopped answering my texts – she doesn’t want to be friends.”

• Criticism. This includes literal criticism, implied criticism, or things that we interpret as criticism.

• Feeling unappreciated. Often not because of what others do – but what they don’t do or say. “I worked really hard to cook a beautiful dinner for my family and they didn’t even come to the table when the food was hot.” Or “You never say thank you for everything I’m doing for the family, and you’re always focused on what I’m doing wrong.”

• Teasing. We can probably all remember a childhood hurt from some form of teasing. Maybe there’s a kind of teasing happening in your adult life that hurts too.

• Betrayal. Whether personal or workplace, extreme or subtle, betrayals make us feel hurt.

• Deception. When we are lied to or feel deceived – particularly if it happens with someone we trust – whether or not we know them well, deception hurts.

So, how does this become applied, how can we use it for our own wellbeing?

One way is this: Think of a recent hurt. Then notice, what was the reason? Was it a combination of a couple of them?

Then, I invite you to do a practice. Write down a simple sentence along these lines,

“I felt hurt when Kim said she couldn’t help me, because it felt like a betrayal.”

“I felt hurt when John said I should try thinking logically sometime, it was hurtful teasing.”

“I felt hurt at the dinner when no one seemed to want to talk to me – because it felt like a rejection.”

Begin with, “I felt hurt when….” and then describe the situation in a short, summary phrase. Then add to it a “because…” phrase, identifying which of the causes of hurt from the list above feels like the best fit.

This kind of simple sentence helps us do three incredibly important things.

#1. We boil down the situation to a short phrase. When we are hurt, we tend to get really lost in all the details of the story, especially as anger, blame or shame rush in. The situation feels complex and intricate. When we boil the situation down to a short phrase, it helps us get a little less invested in our own particular argument or narrative. It helps us be a little less precious about it or attached to our take on the story. I know when I do this there’s a kind of 10,000ft view that starts to set in, “Oh right, this is just one more human situation like so many I and others experience everyday.”

#2. As you write this sentence, you are giving language to how you feel. “I was hurt. I felt hurt when…” This is huge. A host of research shows that when we can give language to our feelings, that helps us regulate them and lessen their intensity. It’s also the starting place from which we can consciously choose how we want to respond to the feeling.

Unacknowledged or unprocessed hurt is like an invisible driver in your car – one who is definitely influencing where the vehicle is going…all while you think you are in the driver’s seat. Unacknowledged hurt affects our mood. Our sense of safety with other people, and in the world. Our general emotional rigidity or flexibility, and more.

Whether you ever say “I felt hurt” to the other party is another matter for another post. But if you are feeling hurt, it is a powerful practice to name the feelings to yourself.

#3. You are saying why you were hurt. It’s illuminating to see the cause of the hurt. Hurt, like fear, causes a strong physiologic response that’s often dizzying and disorienting. We don’t see things particularly clearly, or think so precisely, when we are feeling hurt. This list gives us a way to do a kind of analysis of the situation, and to understand it better.

One qualifier. I find that this can go one of two ways. Sometimes, people’s inner wounded part grabs hold of this language and uses it to reinvest in their feelings of outrage and blame. It’s a subtle difference in tone. You can say, “I felt hurt because I was lied to” in a way that feels like an accusation, and brings a deepening of the wound. Or, you can say it with a spirit of self-compassion and more of an observer’s stance.

One thing I love about this list of causes is that it reminds me I’m far from alone in the experience of hurt. It connects, “I felt hurt, because I was lied to (or criticized, or rejected or whatever it was),” and “that is one of the universal human experiences that makes us feel hurt.”

In other words, I’m using this list of universal causes of hurt to ground myself in the truth that in being hurt for one of these reasons, I’ve had a core human experience. I’m joining billions of other humans who have felt hurt for the same reason. I’m part of something larger. It’s actually rather awe-inspiring.

So we say, “I felt hurt when this happened” as a gentle, hand on heart gesture, an “Oh honey, that was hard. It hurts to feel excluded!” Or, “oh honey, that was hard. It hurts to feel unappreciated.”

As we’ll see in a next post, we don’t dwell there. We don’t stay in that experience for the long-haul. But we do pause there to name our hurt and one of the universal human reasons for it, to honor that, and witness it with compassion. Paradoxically, that’s what allows us to move on from it.

Love,

Tara

*Vangelisti, A. L. (2001). Making sense of hurtful interactions in close relationships. In V. Manusov & J. H. Harvey (Eds.), Attribution, communication behavior, and close relationships (pp. 38–58). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Feeney, J. A. (2004). Hurt feelings in couple relationships: Towards integrative models of the negative effects of hurtful events. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 487–508.

Leary, M. R., Springer, C., Negel, L., Ansell, E., & Evans, K. (1998). The causes, phenomenology, and consequences of hurt feelings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1225–1237.